Group Classifier

This project began as a way of solving a very tedious problem on my abstract algebra final. You can view an interactive version of this iPython notebook on Kaggle

Abelian Group Classifier

Groups are a fascinating branch of mathematics. Put simply, they consist of a set $G$ paired with some operator $*$, such that the set is closed under that operation. In other words,

There are other requirements as well but this one, called closure, is perhaps the most defining. It gives groups their intricate internal structure — the unique way in which the elements relate to each other through $*$.

Let’s cover a little more notation and terminology, and then we can talk about what this classifier does.

Some definitions

- The cyclic group $\mathbb{Z}_n$ or integers modulo $n$ is simply the set of numbers $\{0,1,2,\dots,n-1\}$ with the operation of addition. When two numbers add to a number larger than $n-1$, we simply “roll over” and start counting from 0. For example, in the group $\mathbb{Z}_5=\{0,1,2,3,4\}$ we have that $3+4=2$.

- The direct product of two groups $G,H$ is written $G\times H$ and is the group of ordered pairs $(g,h)$ where $g$ is in $G$ and $h$ is in $H$. For example,

- Note that we can have a direct product of more than two groups, e.g. $\mathbb{Z}_2\times\mathbb{Z}_3\times\mathbb{Z}_5\times\mathbb{Z}_5\times\mathbb{Z}_7$. Also note that the order or size of a direct product is simply the product of the orders of its constituent groups, so $\mathbb{Z}_2\times\mathbb{Z}_3$ would have order 6.

- An abelian group is one in which the operation is commutative, i.e. $a \ast b = b \ast a$.

- An isomorphism is a one-to-one function $f:G\to H$ between two groups that preserves the group structure, which is to say that $f(a \ast b)=f(a) \ast f(b)$ in $H$ for $a,b$ in $G$. Two groups that can be linked by an isomorphism are isomorphic to each other, which is to say that they share the same internal structure.

Not all groups are unlike

This last concept is especially important because groups can contain many different types of elements. The elements can be numbers, functions, movements, or positions of a Rubik’s Cube. But many of them will be isomorphic to each other, and thus share the same structure even if their elements look different from each other.

For example, if we define the function $f:\mathbb{Z}_2\times\mathbb{Z}_3\to\mathbb{Z}_6$ as

we see that this forms an isomorphism — for example, $f((1,0)+(1,2))=f((0,2))=2=3+5=f((1,0))+f((1,2))$.

This gives us a sense in which $\mathbb{Z}_2\times\mathbb{Z}_3$ and $\mathbb{Z}_6$ are the same group, because despite looking different, they share the same underlying structure. This structure can be considered the “fingerprint” of that group, and we consider groups to be meaningfully different only if they have different “fingerprints”, i.e. they cannot be linked by an isomorphism.

The Fundamental Theorem of Finite Abelian Groups

Given the premise that some groups can be represented as other groups through isomorphism, we can explore a theorem worthy of its title:

Every finite abelian group can be uniquely represented as the direct product of cyclic groups $\mathbb{Z}_{p^i}$ , where each $p^i$ is a power of some prime number $p$.

With this result, we’ve been handed the power to know every abelian group of a given order (size), using the prime factorization of that order. For example, we can factorize 36 as $2^2\cdot 3^2$, giving us four unique ways to write 36:

These correspond to the four unique abelian groups of order 36:

And that’s it! That’s all of them. Any abelian group of order 36, whether it be made of numbers, functions, configurations of a puzzle, or colors, will be isomorphic to one of these four. We’ve successfully classified every abelian group of this order. This is precisely what this project sets out to do: list all abelian groups of a given order.

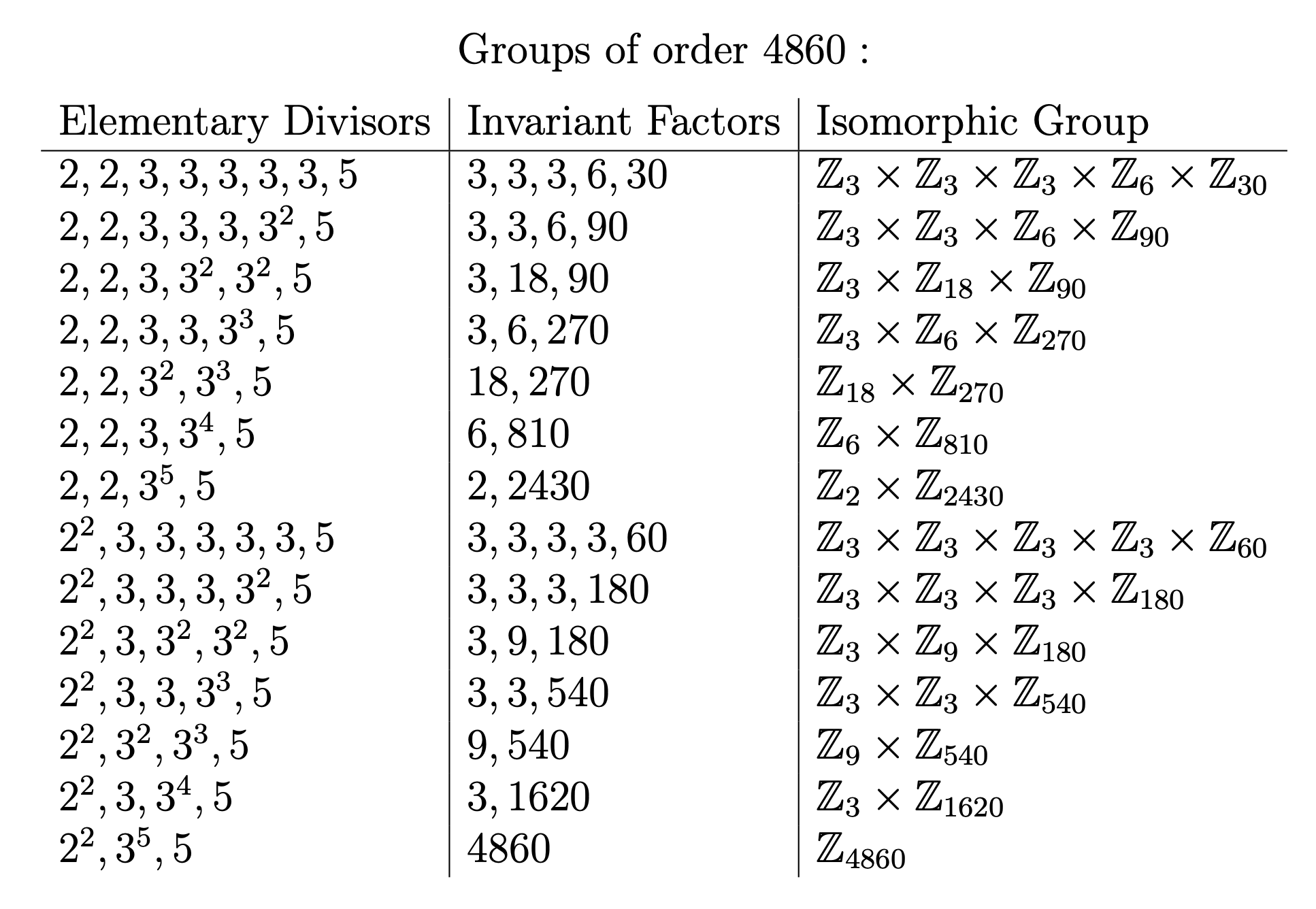

n = 4860

So let’s go ahead and pick an order! I’ve set it to one that gives a nice result, but you can set $n$ to be any whole number between 1 and infinity. You’d be surprised by how many orders only have one unique abelian group associated with them.

Finding the prime factors of $n$ is easy enough to do with a simple iterative algorithm:

n = round(abs(n)) # Just in case you cheated

def prime_factors(number):

divisor = 2

factors = []

while divisor**2 <= number:

if number % divisor == 0:

factors.append(divisor)

number //= divisor

else:

divisor += 1

if number > 1:

factors.append(number)

return factors

factorization = prime_factors(n)

print(factorization)

[2, 2, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3, 5]

For $n=36$ this would return the list [2, 2, 3, 3]. But we want to know the powers of each unique factor, both to reflect the compact notation $2^2\cdot 3^2$ and to help us find all four ways of writing 36.

We can do this using numpy.unique:

import numpy as np

primes, powers = np.unique(factorization, return_counts=True)

size = powers.max()

print(primes, powers)

[2 3 5] [2 5 1]

For $n=36$ this would return the array of unique primes [2 3] with their associated powers [2 2]

Now we need the partitions of each power: the unique ways of writing it as a sum of other numbers. For example, the five unique partitions of 4 are

These correspond to the five unique ways of writing 81, or $3^4$:

After taking a number’s prime factorization, the unique ways of writing it are given by combinations of the partitions of the primes’ powers.

We find these partitions using a recursive algorithm which picks the rightmost number, subtracts it from the total, then uses itself to partition the remaining difference. It also helpfully formats the partition as a sorted array of desired length:

def partitions_oflength(n, length):

if n == 0:

return [np.zeros(length, dtype=int)]

result = []

# Create the trivial partition (all ones)

ones = np.ones(length, dtype=int)

ones[:-n] = 0

result.append(ones)

for j in range(2, n + 1):

# Create the partitions that end with j by

# appending to the partitions of n - j

for p in partitions_oflength(n - j, length):

if p[-1] <= j: # Keep it sorted to avoid duplicates

entry = np.zeros(length, dtype=int)

entry[-1] = j # j at the end

entry[:-1] = p[1:] # p before it

result.append(entry)

return result

print(*partitions_oflength(4,7), sep='\n') # Example

[0 0 0 1 1 1 1]

[0 0 0 0 1 1 2]

[0 0 0 0 0 2 2]

[0 0 0 0 0 1 3]

[0 0 0 0 0 0 4]

Now we just have to make those combinations. We use another recursive algorithm to do this, that makes its way through the list of powers and returns all possible combinations of their respective partitions:

def combos_oflength(P, length):

result = []

header = partitions_oflength(P[0], length)

if P.size == 1:

return header

for x in header:

# For each partition of the first

# given power, add it to the combinations

# of all the following powers

for y in combos_oflength(P[1:], length):

new_combo = np.vstack((x,y))

result.append(new_combo)

return result

def combos(P):

# Pass the largest power to set

# the width of each row

length = P.max()

return combos_oflength(P, length)

partition_combos = np.array(combos(powers))

# Display some of the combinations

n_displayed = 28//partition_combos.shape[2]

print('Some of the power combinations:\n')

for rows in np.rollaxis(partition_combos, 1):

print(*rows[:n_displayed], sep=' ')

Some of the power combinations:

[0 0 0 1 1] [0 0 0 1 1] [0 0 0 1 1] [0 0 0 1 1] [0 0 0 1 1]

[1 1 1 1 1] [0 1 1 1 2] [0 0 1 2 2] [0 0 1 1 3] [0 0 0 2 3]

[0 0 0 0 1] [0 0 0 0 1] [0 0 0 0 1] [0 0 0 0 1] [0 0 0 0 1]

For $n=36$ this would return the four possible combinations of the partitions of 2 and 2:

[1 1] [1 1] [0 2] [0 2]

[1 1] [0 2] [1 1] [0 2]

As a reminder, these correspond to the four representations

\begin{array}{cccc} 2\cdot 2\cdot 3\cdot 3\qquad & 2\cdot 2\cdot 3^2\qquad & 2^2\cdot 3\cdot 3\qquad & 2^2\cdot 3^2 \end{array}

This should be all we need to classify our groups. However, there’s one more thing we need to consider.

Surprise! Another theorem

More of a lemma, really. This one’s pretty simple:

If two numbers $m,k$ are coprime, meaning that no number greater than 1 divides them both, then $\mathbb{Z}_m\times\mathbb{Z}_k$ is isomorphic to (meaning, functionally the same group as) $\mathbb{Z}_{mk}$.

This really complicates our task. It means that the groups

It means that after we’ve found our groups, we have to condense them until their constituents all share a common divisor. We do this by turning their elementary divisors, e.g. $2^2,3,3$ into invariant factors e.g. $3,12$.

The invariant factors have the property that when sorted from least to greatest, each number divides the number after it. They also provide a unique representation of the group: each set of elementary divisors is associated with one and only one set of invariant factors.

One more algorithm

To find the invariant factors, we have an interesting algorithm which exploits the fact that for distinct primes $p_1,p_2,…,p_i$ which make the product $n=p_1^{n_1}p_2^{n_2}\cdots p_i^{n_i}$, the group $\mathbb{Z}_{p_1^{n_1}}\times\cdots\times\mathbb{Z}_{p_i^{n_i}}$ is isomorphic to $\mathbb{Z}_n$ (this result follows from the theorem we just introduced).

Consider the group

we can condense this group by making a table with a row for each prime, thus separating any duplicates:

Then we can take the product of each column, which will have the combination of distinct prime powers we’re looking for. By arranging them left-to-right by size, we also guarantee that each product will divide the next. In this example, we get the invariant factors 2, 6, 60, and 600, so our group is

Once we have a combination of powers we’d like to condense, we can create the table and multiply the columns in just two lines using NumPy. Or more accurately, we can do this for every combination at once:

X = np.repeat(primes[:,np.newaxis],size,1)

divisor_tables = X**partition_combos # Broadcasting!

# Flatten all the tables at once by picking the right axis

factor_lists = np.prod(divisor_tables, 1)

Now we just need to display all our hard work. We could do this by creating a DataFrame in Pandas, but LaTeX always looks best:

from IPython.display import Latex

# Set up the table in LaTeX

output = r'$\text{' + f'Groups of order ' + r'}' +f'{n}$:\n'

output += r'''

\begin{array}{l|l|l}

\text{Elementary Divisors} & \text{Invariant Factors} & \text{Isomorphic Group}\\

\hline'''

# Create the entries by piecing together some strings

for combo, factor_list in zip(partition_combos, factor_lists):

divisors = ''

for divisor, power in zip(X.flatten(), combo.flatten()):

if power > 0:

divisors += ',' + str(divisor.item())

if power > 1:

divisors += '^' + str(power.item())

output += '\n ' + divisors[1:]

factors = ''

group = ''

for f in factor_list[factor_list != 1]:

factors += str(f.item()) + ','

group += r'\mathbb{Z}_{' + str(f.item()) + r'}\times'

output += f' & {factors[:-1]} & {group[:-6]}' + r'\\'

output += r'''

\end{array}'''

Latex(output)